I served for 41 years in law enforcement, retiring in 2016.

I served for 41 years in law enforcement, retiring in 2016.

As an officer I labored for the federal side and the local side. Whilst in Detectives I happened to work in Theft, Warrants, Child Abuse, Sex Assaults, Robbery and finally Homicide. I had to get arrest warrants. I had to get search warrants. I had to write and submit affidavits and warrant requests with my hero pages. If I had to do it, the rest of law enforcement should have to do it. I had to respect the 4th Amendment. All of law enforcement should have to respect the 4th Amendment.

From the WashingtonTimes.com:

From the WashingtonTimes.com:

Supreme Court rules warrant required for cellphone location data

by Alex Swoyer

The Supreme Court on Friday said the government must obtain a search warrant before demanding an individual’s cellphone location records from a telecommunications company.

In the 5-4 decision, the court said it’s a violation of the 4th Amendment for police to search a suspect’s cell-site location information (CSLI), which is stored by a telecommunications company, without a warrant.

The case arose when a defendant was convicted of a series of robberies based on his cellphone location data. He moved to suppress the evidence, saying the records were obtained without a warrant and thus violated his 4th Amendment protection.

The lower courts sided with the government, but the high court decided the 4th Amendment’s guarantee to privacy extends to new age technology.

“A person does not surrender all Fourth Amendment protection by venturing into the public sphere,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts wrote in the court’s opinion.

Yes, I was in law enforcement. But I had to obey the law. On the federal side I could acquire pen registers and Title IIIs. With warrant requests and applications. And they came with serious limitations “back in the day” when you had reel-to-reel recorders. You couldn’t just activate the recorder and perch all day. You could only listen for a brief time and then switch off if you heard nothing. Timing was everything.

Technology is confounding, certainly. But law enforcement can get lazy and can’t afford to. My advice to cops: don’t get lazy. On homicide scenes, depending on the case, I may have had possession of a house or a certain scene but in order to buttress my case I also went to a judge and acquired a search warrant to make my investigation more bulletproof.

The government had argued the information was kept by a third party, the telecommunications company, so it did not violate the suspect’s 4th Amendment rights.

This isn’t rocket science. Everyone knows that most people leave the GPS activated on their cell phones and by doing so the cell provider knows, generally, where the phone — and hence you — are located. Truly, you don’t even have to activate GPS. The cell towers just know.

But the court said a company’s constant tracking of an individual carries concerns.

“In light of the deeply revealing nature of CSLI, its depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach, and the inescapable and automatic nature of its collection, the fact that such information is gathered by a third party does not make it any less deserving of Fourth Amendment protection,” Justice Roberts wrote.

He was joined by the courts’ four Democratic appointed justices, but the court’s four Republican appointed justices disagreed with the holding.

This next bit of information aligns with my way of thinking and the analogy is proper and correct.

The ruling follows a case six years ago where the court said a GPS tracking device on a suspect’s vehicle without a warrant is unconstitutional.

Allow me to go a bit further. Your cell phone is much more than a simple communications device that allows you to talk to people. It is a texting machine, a camera, an audio recorder, a video recorder and, frankly, a computer. People have their lives in their cell phones these days. Breaking into someone’s cell phone is not unlike breaking into their personal computer at home.

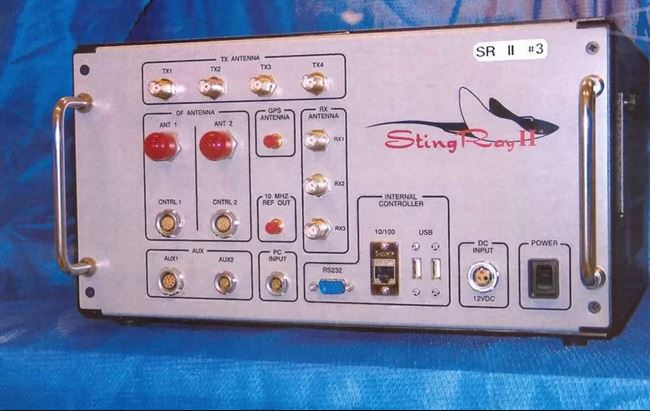

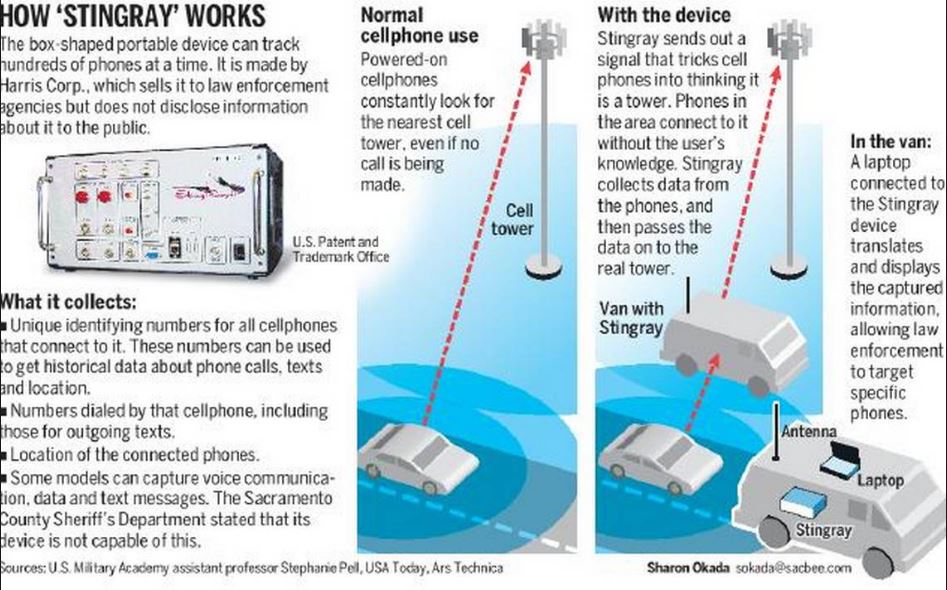

Also, quite a number of law enforcement agencies have Stingrays these days. This is a device called an IMSI catcher. It can be used to track and locate cell devices and users, block signals, intercept communications content, force cell phones to disconnect from their standard carriers and connect to it — and a host of other functions. See the graphic.

Also, quite a number of law enforcement agencies have Stingrays these days. This is a device called an IMSI catcher. It can be used to track and locate cell devices and users, block signals, intercept communications content, force cell phones to disconnect from their standard carriers and connect to it — and a host of other functions. See the graphic.

If you’re in or near an urban center and not under the flight pattern of a military base or commercial airport, you know that air traffic is a fraction of what it used to be when I was growing up. To even see a military aircraft these days is an uncommon occurrence. But have you ever heard a small plane buzzing about at night in what seems to be some kind of a pattern for a lengthy period of time?

If you’re in or near an urban center and not under the flight pattern of a military base or commercial airport, you know that air traffic is a fraction of what it used to be when I was growing up. To even see a military aircraft these days is an uncommon occurrence. But have you ever heard a small plane buzzing about at night in what seems to be some kind of a pattern for a lengthy period of time?

Chances are pretty good that its occupants work for a federal, state or local law enforcement agency and that they are employing a Stingray or a variant.

This, then, is of note from Engadget.com:

Court rules Stingray use without a warrant violates Fourth Amendment

by Mallory Locklear

The ruling could have widespread implications for the technology.

Today, the Washington DC Court of Appeals overturned a Superior Court conviction of a man who was located by police using a cell-site simulator, or Stingray, CBS News reports. The court ruled that the defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights were violated when law enforcement tracked down the suspect using his own cell phone without a warrant.

Stingrays work by pretending to be a cell tower and once they’re brought close enough to a particular phone, that phone pings a signal off of them. The Stingray then grabs onto that signal and allows whoever’s using it to locate the phone in question. These sorts of devices are used by a number of different agencies including the FBI, ICE, the IRS as well as policeofficers.

The use of cell-site simulators, especially without a warrant, has come under question a few times in recent years. In 2016, a federal judge suppressed DEA evidence obtained via such a device, the first time a federal judge had done so. Last year, members of Congress called for legislation that would protect citizens’ privacy and require a warrant before Stingrays could be used by law enforcement. Two such bills were introduced in the House of Representatives earlier this year.

Obviously, this is my Libertarian side coming out. I am a great advocate of privacy — and why I say:

When I was a law enforcement officer, I had to acquire search warrants. There is no reason current law enforcement shouldn’t do the same thing. It will help your case to acquire even more strength. If you lack PC for said warrant, you’d best start rethinking your case.

When I was a law enforcement officer, I had to acquire search warrants. There is no reason current law enforcement shouldn’t do the same thing. It will help your case to acquire even more strength. If you lack PC for said warrant, you’d best start rethinking your case.

BZ