Get some headphones, turn up the volume.

Celebrating 55+ years of service — perhaps even 90 years of service?

How B-52 Bombers Will Fly Until the 2050s

by Kyle Mizokami

The Air Force’s fleet of Cold War bombers will fly longer than most people will live, allowing B-52 crews to work on planes their great-grandfathers flew.

A series of upgrades to the B-52 Stratofortress bomber could keep the remaining fleet of Cold War bombers going until 2050. The planes, built during the Kennedy Administration, are expected to receive new engines, electronics, and bomb bay upgrades to keep them viable in nuclear and conventional roles.

The B-52 strategic heavy bomber is a true survivor. It was designed to fly high over the Soviet Union carrying atomic bombs if necessary. But the B-52 is the do-it-all tool of strike warfare, taking on whatever mission is popular at the time.

Get a load of this:

B-52s were modified to drop conventional bombs during the Vietnam War, where they proved they could fly low to penetrate enemy defenses, gained the ability to drop precision-guided bombs, and swapped their nuclear bomb loads for nuclear-tipped cruise missiles. The B-52s also can carry Harpoon anti-ship missiles, lay minefields at sea, and provide close air support to troops on the ground. B-52s have even flirted with air-to-air warfare, with their tail gunners reportedly shooting down two MiG-21 fighters over Vietnam.

Tail gunners. Actual tail gunners. We’re talking primeval WWII aircraft having tail gunners.

So why keep an ancient relic like the Boeing B-52?

How would the B-52 use all of this new equipment to stay relevant on the battlefield? As a large aircraft with the radar signature of a barn door, adversaries can see a B-52 coming from miles away. That said, a B-52 can fire missiles like JASSM from beyond radar detection range. In wartime, a B-52 could work with a stealthy aircraft like the F-35 to launch missiles against time-sensitive targets. A F-35, while flying stealthy, can carry a limited amount of weapons, but it could spot targets at sea or on the ground and relay targeting data to a B-52 hundreds of miles away.

The LATimes.com even surmises the B-52 will fly for a full century:

Why the B-52 bomber will fly for 100 years

by Justin Bachman

The Air Force just can’t let go of the B-52.

In the world of heavy bombers, none has prevailed as long as the B-52 Stratofortress. The Cold Warrior joined the U.S. arsenal in 1954, eventually becoming part of a nuclear triad that, along with strategic missiles and submarines, was aimed at giving the Soviet Union pause. After the Berlin Wall fell, it slowly became an aerial jack-of-all-trades. With its long range, minimal operating cost and ability to handle a wider array of weapons than any other aircraft, it just didn’t make sense to get rid of it.

Under the Air Force’s current bomber plans, the B-52 will fly until 2050 — just shy of its 100th birthday. While this prospective centenary has been cause for some breathless coverage, little has been said about how a complex piece of machinery built during the Korean War is still useful in 2018, let alone 2050. What is the B-52’s secret?

That secret is flexibility. Boeing Co. produced more than 740 B-52s since the first one rolled out. It’s had many nicknames — the most apt at this moment being “Stratosaurus.” Like any other well-regarded employee who manages to survive, and even thrive, in a constantly changing organization, the B-52 has always found an important role.

But what’s next? Right. The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider. But it ain’t no B-52.

At the pricier end of the spectrum, the Pentagon is budgeting almost $17 billion over the next five years to develop the new B-21 Raider from Northrop Grumman Corp., which will replace the current fleet of B-1B Lancer and B-2 Spirit bombers. The B-21, which may fly as a “crew-optional” aircraft, is expected to join the Air Force fleet in the mid-2020s. The Pentagon plans to buy at least 100 B-21s, spending about $97 billion.

That spells the end of the B-52. Right?

Backing it up will be the Stratosaurus.

The decisions were detailed this week as part of the Trump administration’s budget request to Congress. The 1980s-era supersonic B-1 and the radar-evading B-2 fielded a decade later will be phased out gradually as new B-21s enter service, Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson said.

Wait for it.

The B-21 will offer the U.S. the ability to strike with speed and stealth, “but once we own the skies, the B-52 can drop ordnance better than most others,” Ferguson said. “And hey,” she added, “it’s paid for.”

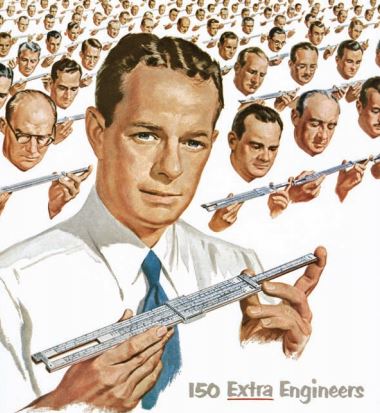

It looks like the analog era of geeky white males with thick glasses, protractors, slide rules, pocket protectors and short-sleeved white shirts with thin ties may have been ahead of their time.

It looks like the analog era of geeky white males with thick glasses, protractors, slide rules, pocket protectors and short-sleeved white shirts with thin ties may have been ahead of their time.

BZ

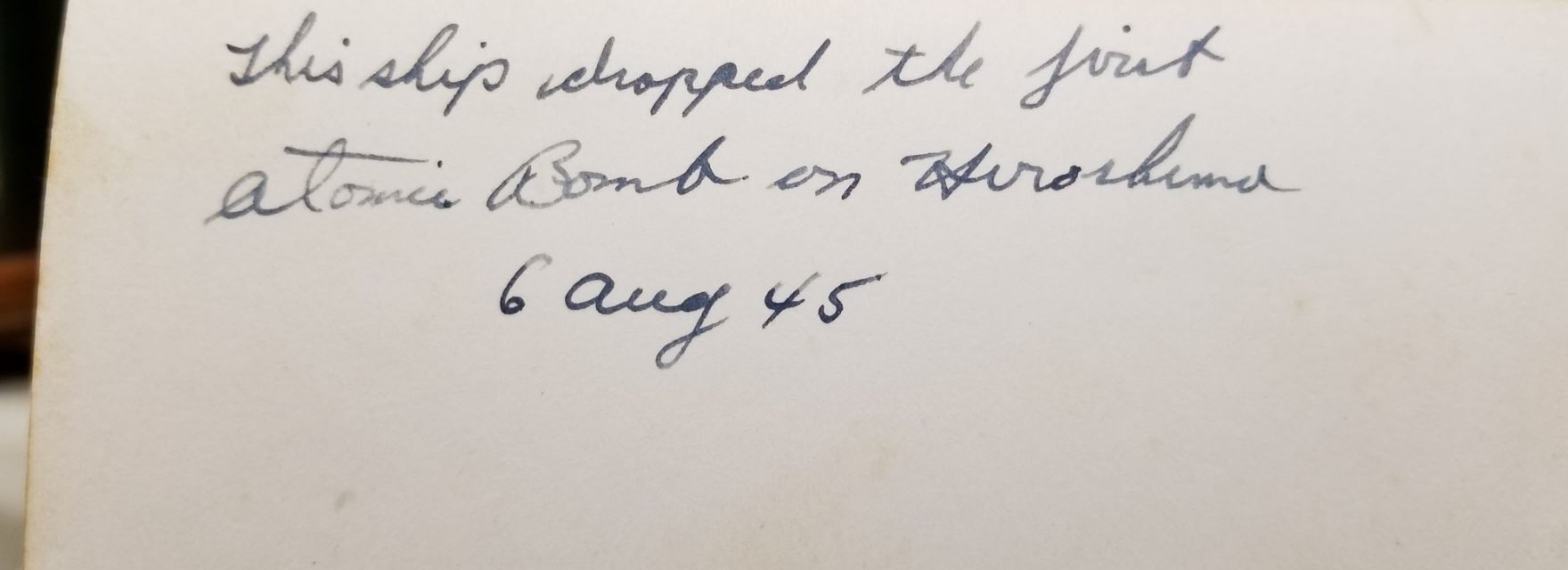

He took this photo himself. He never told me where he was or how he managed to acquire the photograph. I possess the original.

He took this photo himself. He never told me where he was or how he managed to acquire the photograph. I possess the original. How did my father manage to do this? I have no idea. I only found these photographs a few years after he passed away in 2009 at the age of 88.

How did my father manage to do this? I have no idea. I only found these photographs a few years after he passed away in 2009 at the age of 88. Imagine being a passenger.

Imagine being a passenger.